135 years to go before women have the same rights as men

Ensuring equality in decision-making, eliminating gender-based violence and closing the wage gap between men and women should no longer be an issue in any society in the 21st century. The world moves at different speeds and while in the European Union it will “only” take 60 years to achieve gender equality, the global average shows that this ideal is still far out of reach and will only become a reality in 2157, assuming there are no setbacks such as those caused by the pandemic.

Gender Equality. This is the fifth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) stipulated by the United Nations (UN). And at first glance it seems quite a “simple” goal. Simple because it relates to ending all forms of discrimination against women and girls around the world; ending all violence against females in the public and private arena, including sex trafficking and exploitation. It also addresses the eradication of harmful practices, such as forced marriages involving children, as well as female genital mutilation. These problems arise in other parts of the world, but are not relevant in Europe and Portugal. The same cannot be said for other issues which also fall under the 5th SDG, such as recognising and valuing unpaid assistance and domestic work, and ensuring the full and effective participation of women and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life, and assuring universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights. It is also the UN’s goal to implement reforms to give women equal rights to economic resources, increase the use of basic technologies to promote female empowerment and adopt and strengthen sound policies and applicable legislation to promote gender equality.

The need for goals

Why does the United Nations have to set out these rights in such detail, in the form of goals? To put it bluntly, because even in the 21st century, women still face more discrimination than men. Whether because they are subject to sexist comments, because they have fewer opportunities to access decision-making positions, or because they face greater social pressure to juggle housework and a job. Indeed, unpaid care undertaken by women represents almost double that undertaken by men in OECD countries. According to a study by the Manuel Francisco dos Santos Foundation, based on its own data, women in Portugal do on average 74% of the household chores while the men with whom they live do an average of 23%.

In education, for example, mothers also account for more than triple the amount of work done by fathers. Women take care of 73%, on average, of tasks relating to caring for and educating their children, and men just 21%. The remaining 6% of jobs are done by relatives or paid help. 35% of couples with children split childcare evenly.

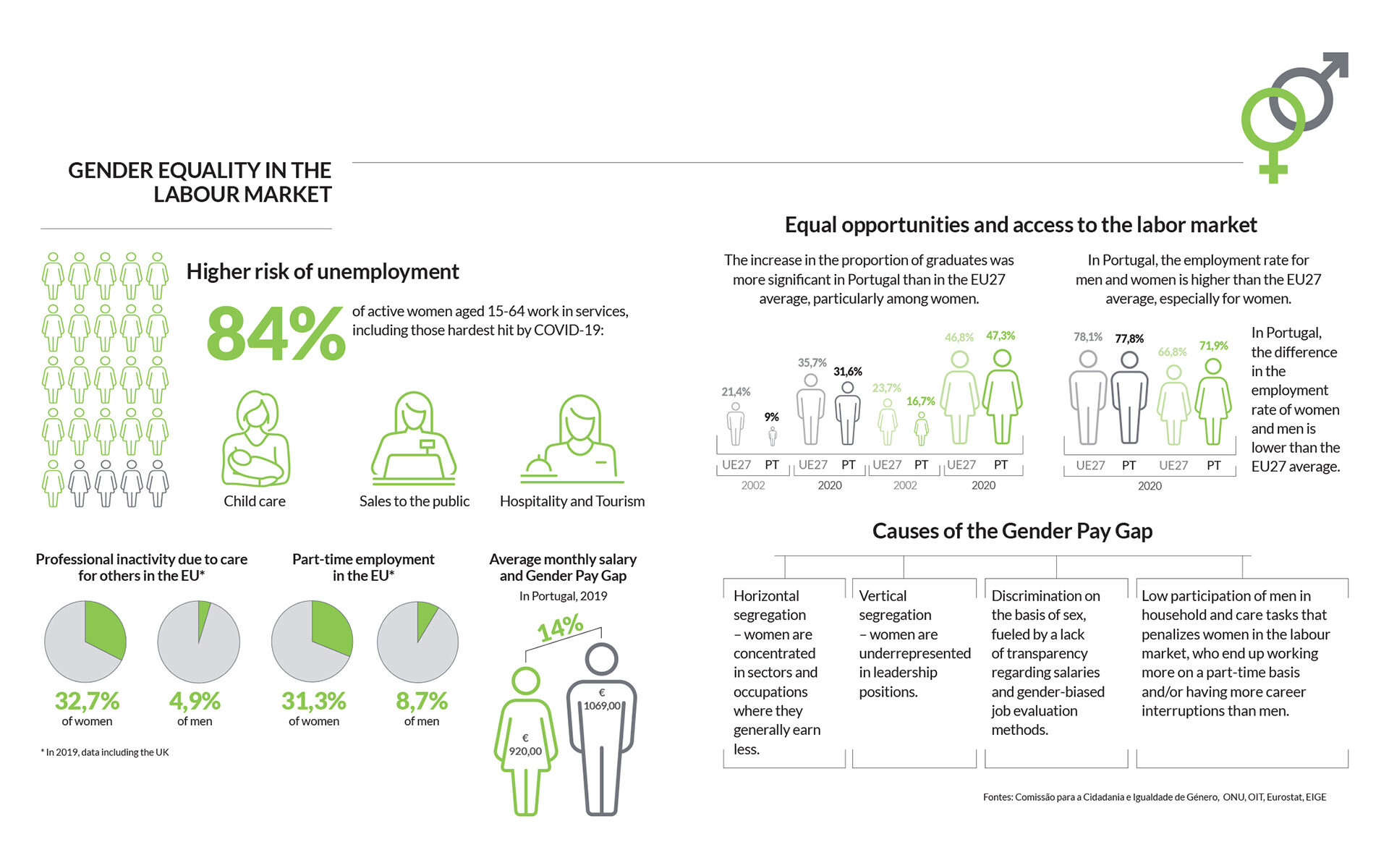

In the EU, women’s hourly pay is on average 14% lower than men’s.

In fact, according to this study, the pace at which the last generation has evolved in terms of men contributing towards housework, means that there are five to six generations to go before men and women become equal in couples where both work outside the home. In younger couples, where the woman is aged between 18 and 40, the man bears a slightly greater load than those where the woman is over 40 (the former, on average 26%, and the latter 22%). However, there has been no change in terms of fathers’ contribution towards children’s education during the last generation. This is how things stand in Portugal. And what of Europe?

Europe making shaky progress

In 2021, the European Union scored 68 points out of 100 in the Gender Equality Index, disseminated in October by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). The 0.6 point increase since 2020 was deemed “microscopic”. At the time, the head of the EIGE, Carlien Scheele, was of the view that Europe had made shaky progress in the field of gender equality. She warned of the impact the Covid-19 pandemic was having on women. “The economic consequences are being more drawn-out for women, while life expectancy for men has fallen.” We’ll come back to Covid later. Just a heads-up: the pandemic set gender parity back a generation.

In Europe, Sweden and Denmark are performing the best in this index, followed by the Netherlands which overtook Finland and France. Luxemburg, Lithuania and the Netherlands showed improvements in 2021, and Slovenia was the only country to slide backwards. “The gender equality scores vary greatly from country to country, from the highest of 83.9 points in Sweden to the lowest of 52.6 points in Greece.” Portugal came in at 62.2 points, compared with Spain’s 73.7.

Parity is a long way off

According to the EIGE’s Gender Equality Index, gender parity will be achieved in the European Union within 60 years. In the rest of the world, the picture is very different. The Global Gender Gap Report 2021 by the World Economic Forum states that the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic is still being felt. The gender gap increased by the length of a generation: instead of 99.5 years, it will now take 135.6 years to close the gap.

Indeed, the Forum states that progress towards gender parity has stagnated in many major economies and industries. “This is partly down to the fact that women more often work in those sectors more affected by lockdowns, combined with the added pressures of providing care in the home.”

The 15th such report by the WEF compares the evolution of gender differences in four areas: economic participation and opportunity; educational attainment; health and survival; and political empowerment. The document reports that the deterioration in 2021 is partially attributed to growing political gender disparity in several different highly-populated countries. Although more than half the 156 indexed countries recorded improvements, women still only occupy 26.1% of seats in parliament and 22.6% of ministerial positions worldwide. If we continue along this trajectory, gender equality in the realm of politics will take 145.5 years to achieve, rather than the 95 years predicted in the 2020 report – an increase of over 50%.

CHRONOLOGY OF GENDER EQUALITY POLICIES

1975

The United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination is approved by the UN General Assembly. Portugal ratifies this Convention in 1975. This is one of the great Human Rights Treaties and is often referred to as the Magna Carta of Women’s Rights or the Bill of Rights for Women.

1993

Viena hosts the UN World Conference on Human Rights, which recognises that “The human rights of women and of the girl-child are an inalienable, integral and indivisible part of universal human rights” (Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, 1993, §18).

1995

The UN World Conference on Women, Development and Peace is held in Beijing, which adopts the Beijing Platform for Action aimed at implementing women’s rights around the world.

2015

The UN passes Agenda 2030 and stipulates the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). The gender issue is considered to apply to the entire agenda and constitutes the 5th SDG: “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls” (UN, 2015).

Enormous economic disparity

Economic disparity showed only a marginal improvement since the 2020 report, and equality should be achieved in 267.6 years’ time. According to the report summary, “the slow progress is down to opposing trends – although the proportion of qualified professional women continues to grow, pay differences remain and few women are represented in management roles.”

Although the World Economic Forum is “concerned” about these findings, gender differences in education and health are becoming less obvious. In education, while 37 countries have reached gender parity, it will take a further 14.2 years to close this gap completely because progress is slowing down. In health, over 95% of this gap has been eliminated, with a marginal decline since last year.

There are fewer women in executive positions: fewer than 10% are CEOs at top companies.

“The pandemic has fundamentally impacted gender equality in both workplace and the home, rolling back years of progress”, says Saadia Zahidi. “If we want a dynamic future economy, it is vital for women to be represented in the jobs of tomorrow. Now, more than ever, it’s crucial to focus leadership attention, commit to firm targets and mobilise resources.”

Covid-19’s impact on women

The pandemic had a more negative effect on women than on men, with women losing their jobs at higher rates (5% vs. 3.9% for men, according to the International Labour Organisation), partly down to women being more heavily represented in sectors more directly disrupted by lockdowns, such as the consumer sector. Data from the United States also indicate that women from historically disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups are most affected. Furthermore, information arising from a study undertaken by market research company Ipsos, suggests that when care facilities were closed down, housework, childcare and caring for the elderly fell disproportionately on women, contributing towards higher stress levels and lower productivity.

As the job market recovers, LinkedIn data shows that women are being hired at a slower rate in multiple sectors. Women are also even less likely to be hired for leadership roles, resulting in a reversal of up to two years’ progress.

Women in emerging jobs

Sectors with historically low levels of women are also those considered the fast-growing “jobs of tomorrow”, according to the World Economic Forum report. In cloud computing, for example, women currently make up 14% of the workforce; in engineering, 20%; in data and artificial intelligence, 32%; and it’s harder for women to switch to these emerging roles than it is for men.

56% of the time women are awake at home is spent doing unpaid work. This translate into 3h48 per day, on weekdays.

“Women aren’t well represented in the majority of fast-growing roles, which means we are storing up even bigger gender representation problems as we emerge from the pandemic. These roles play a significant part in shaping all aspects of technology and how it is rolled out around the world,” says Sue Duke, head of global public policy at LinkedIn in response to the report. “Women’s voices and perspectives just need to be represented at this foundational stage, especially as digitisation is accelerating. Companies and governments need to incorporate diversity, equity and inclusion into their plans for recovery. It is vital that candidates be assessed on their skills and potential, and not just on their direct work experience and formal qualifications. Skills-based hiring is key if we’re going to make our economics and societies more inclusive.”

Is there light at the end of the tunnel?

Yes, there is. On 21st January 2021, members of the European Parliament passed a resolution on the EU’s Gender Equality strategy, requesting the European Commission to draw up a new and ambitious plan of action to tackle the gender pay gap, which should set clear targets for Member States to shorten their gaps over the next five years.

Of the EU’s 49 million healthcare workers who were exposed to the virus, around 76% were women.

Furthermore, the European Parliament wants to make it easier for women and girls to study and work in male-dominated fields, to ensure more flexible work hours and to improve wages and working conditions in areas which attract more women. There is light at the end of the tunnel. We just hope it doesn’t take 135 to get there.

The global gender gap in 2021

According to the Global Gender Gap Report 2021, Iceland is – for the 12th time – the world’s most gender-equal country. The five countries which have most improved their scores in the global index in 2021 are Lithuania, Serbia, East Timor, Togo and the United Arab Emirates, which all reduced their gender inequalities by 4.4% or more. East Timor and Togo also managed to close their economic gap by at least 17%.

Western Europe is still the best performer and even improved further, with 77.6% of gender inequality no longer an issue. At this rate, the gender gap will be closed in 52.1 years’ time. Six of the 10 main countries in the index are located in this part of the world, and the improvements seen in 2021 are down to the fact that 17 of the 20 countries in this region boosted their performance at least slightly.

North America (76.4%), comprising Canada and the United States, is the region which saw the most improvement, rising by almost 3.5%. As a result, it will require 61.5 years to close the gap. A significant part of the progress made this year relates to reduced political gender disparity, having narrowed from 18.4% to 33.4%.